“Because the mask is your face, the face is a mask, so I’m thinking of the face as a mask because of the way I see faces is coming from an African vision of the mask which is the thing that we carry around with us, it is our presentation, it’s our front, it’s our face.”

– Faith Ringgold

What do we think of when we think of science and technology? Living currently in our high-tech, digital world with computers, the Internet, techies and laboratory scientists, many of us separate ourselves from science and technology as if they are not part of our everyday lives. Do we think of a mask as technology? I want to explore that idea.

A few weeks ago, I began reading Tempestt Hazel’s Black to the Future Series in which she interviews artists and intellectuals about Afrofuturism and Afrosurrealism. While reading some of the answers of the interviewees, I recognized a subtle framing of and at times distancing from Afrofuturism based on electric and digital technology of the 20th and 21st century. Phrases like “I’m not a techie,” in a sense undermines how much science and technology are embedded in the creation of our lives and that they have existed longer and have a wider reach than we normally think. As the aesthetic movement of Afrofuturism gains recognition, we need to break down the boundaries of what we describe as science and technology.

Last year, I attended The Festival of the New Black Imagination where futurist Nat Irvin II gave a lecture on the importance of futuristic thinking that included a history of science and technological advancement, beginning with the Agricultural Revolution, which could also be called biotechnology. He claimed that only now we have reached an age of hybridity where man and machine are coming together.

Thinking back on that claim, I have come to disagree. We have always been hybrid creatures or cyborgs as Amber Case discussed in her lecture about prosthetic culture and cyborg anthropology. To say that only now we are, is to think in the same linear Western sense in which racists tell societies they consider primitive that Western culture brought them science and technology.

Science and technology are much more than machines and computers. If you look at the definition of both terms, their meanings are more inclusive. Science is the knowledge or a system of knowledge covering general truths or the operation of general laws. Technology is the science of the application of knowledge to practical purposes or applied science.

Machines and computers are tools and instruments, which are all applied knowledge for specific purposes. Referring back to the theme of my post, how does that relate to the mask? Since technology is an application of knowledge, or, in other words, an extension and expression of one’s abilities and thoughts, then so is a mask, in both its creation and use.

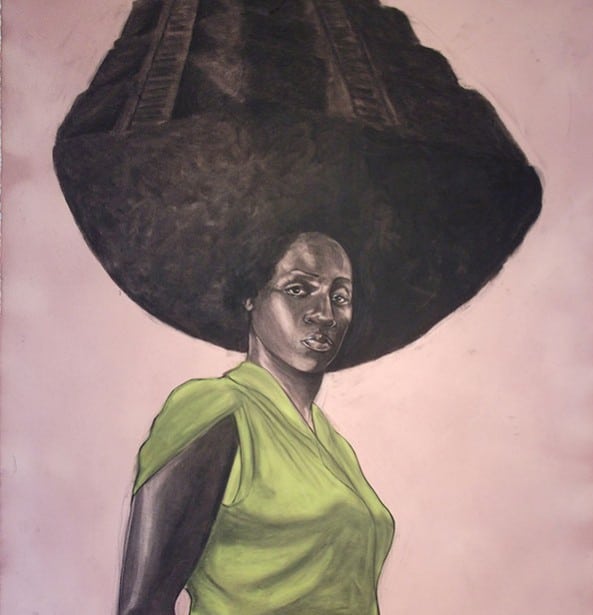

Robert Pruitt’s Towards a Walk in the Sun

Many of us may think of a mask as only art or an object used in a religious ritual, but it is a tool or instrument applying some sort of knowledge as well. Like the mask, technology works as a medium; they let us do things we would not be able to do without them. A mask is an alternate face similar to prosthetic limbs, electronic pacemakers and even musical instruments that extend our bodies’ abilities. Astronauts and scuba divers basically wear masks and costumes that allow them to go where a normal human being would not be able to go. The mask shows us that we are cyborgs (cybernetic organisms). We are part natural and part created; we have been since as early as the agricultural revolution. This is the reason I disagreed with Irvin; any tool we have used has been an extension of us.

Rethinking of science and technology can also help us to rethink our views of our bodies and on religion. Think of it in terms of the Lucius Brockway’s line from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man: “We the machines inside the machine.”

Often art, the body and religion are positioned as the opposite or outside of the realm of these things, but I agree with ethnomusicologist Kyra Gaunt when she said in Games Black Girls Play that musical instruments and bodies are also forms of technology. Our physical bodies are manifestations of thoughts, knowledge, memories, experiences. Since we take in information from the world, the mind analyzes it and the body evolves accordingly. The development of our opposable thumbs, which allows us to create all the technology we have, can be considered a technological development.

In terms of religion or cosmology, for those who believe in a god or some sort of divine consciousness, creator or designer, and for those who believe we are spirits having a physical experience, our body then can be considered a tool or medium of a spirit of God. And if God is a creator or designer much like we are, then it is not perfect, but constantly experimenting and re-inventing itself based on its experience. This can connect creationism and evolution together. Also, depicting ourselves as both spirit and body represents another form of the hybridity that I discussed earlier.

As we look at our cultures through the lens of Afrofuturism and encourage younger generations to learn more about science and technology, I also encourage that expand on these to explore our cultures’ pasts, presents and futures. Re-evaluating our scope of and how we relate to science and technology could benefit us in the long run. They are more than the current advancements that developed in the industrial and post-industrial eras and that are exclusive to dominant cultures, upper classes and capitalists. All types of science and technology, whether it be in the form of a mask or a computer, allow us to fantasize about, explore and experience possibilities as well as understand ourselves and the world around us better.

Interview

1. How do you define technology? How do you define Afrofuturism? How do you participate in Afrofuturism?

My definition of technology came from reading Kyra Gaunt’s book, The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes From Double-Dutch to Hip-Hop while writing my undergraduate thesis on The Percussive Approach in Hip-Hop. In her third chapter, Mary Mack Dressed in Black: The Earliest Formation of a Popular Music, one of the subsections was the “body as technology.” Here she describes her view on technology in terms of black musical production:

“In this way and others, the body is a technology of black musical communication and identity. Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines “technology” as “the practical application of knowledge, a manner of accomplishing a task (i.e., identifying with blackness, the African Diaspora, Africans), using a skill or craft, a method or process” (1999). Extra-somatic instruments … are acceptable media of artistic technology. The social body as a tool or method of artistic composition and performance, however, continues to be overlooked in the study of music … ” (59).

She continues to say how extra-somatic musical technology are extensions of what our bodies and voices naturally can do. Reading her words broadened my scope of what technology is and part of the inspiration for my post, The Mask as Technology. Technology is the application of knowledge and wisdom through the invention of extensions that compensate for our needs and desires and that reach across limitations and boundaries.

For centuries, Black bodies have been exploited as forms of slave/capitalist technologies, designed for the desires of white hetero-patriarchal cultures. Although I don’t tend to give Afrofuturism a specific definition as it means different things to different people, I view it as a tool, a kind of technology as well. I use it to reclaim our whole bodies (physical, mental, spiritual) through the exploration of various possible futures and presents in addition to revising or revealing (the meaning of apocalypse) various pasts of the African Diaspora using tropes of current speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, myths, legends, folktales, fairy tales, historical revision), magic(k), spiritual systems, science and technology.

I participate in Afrofuturism through my writing and studies, including my blog, Futuristically Ancient. I see myself as a kind of archivist, linking the past and future through recording the arts and cultures of the Diaspora that the mainstream may ignore or degrade to show Blackness and the Diaspora outside the box of expectations in which they are placed. What we have been told about who Black people and African descendants by others are filled with untruths used to control us and the imaginations of ourselves and what we can be and do; I want to show the various possibilities of Blackness and Black people that has already existed, still exist and will exist if we fight for it.

2. One criticism about Afrofuturism is that it does not advance technology or dream up novel technologies that can have practical, real-life applications. What are your thoughts on this critique? How does Afrofuturism/Black futurism inform your research and real-life work?

I wonder how Afrofuturism is perceived or used in their questioning. Are they using it as a singular movement or word in which they see only a small segment or its mainstream advocates, and then ask why they do not see a specific aspect there that they would like to see? Or do they see it like I do, as a tool to explore various areas and ideas of cultures of Black people and African descendants in and out of the mainstream that could result in those inventions. I know that there are people out there who are imagining or inventing new technologies because we are humans and humans are constantly engineering new technologies. We are inventive people who survive in times of necessity and within oppressive societies, in music, food, spirituality, electronics (think early days of hip-hop and rewiring the streets to power turntables), etc.

The focus should be redirected from inventing new technologies, because that will always come, to the cultures, spirituality, ethics and values around those technologies. How do we shape minds to think outside of the boxes of the oppressive cultures in which we live and develop responsible technologies? How do we cultivate cultures and critical thinking that will foster new technologies? How do we make available access to information, spaces and tools that will help people to create new technologies? It reminds me of Amiri Baraka’s essay, Technology and Ethos, where he says our machines are extensions of us, the creators, so they reflect our core values. Why does the typewriter look the way it does and why does it not function in another way? he asks. A lot of how we see technology is steeped in Western thought of efficiency, progress and making capital and not how it enriches our lives, the lives of other animals, plants and the Earth. We still have a lot of unlearning to do.

Afrofuturism has centered my thoughts, giving me an angle from which I could process them and research new ideas. It has allowed me as a writer to explore outside of conventional, singular narratives of Blackness, of gender, of sexuality, of culture, of religion and spirituality, of science and technology, of the construction of narratives themselves and so forth. Through it, I have a fresh way to look at the cultures of the world, including my own as an Afro-Caribbean-American woman, not through the mainstream’s eyes, but with eyes of understanding and connection. For example, I see now the genius of African-derived spirituality and religions like Vodou, which is often demonized and simplified through Christian morality and racist philosophy (and I was guilty of that as well); my research into it formed the basis of my upcoming essay, ‘The Electric Impulse:’ The Legba Circuit in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. Afrofuturism was also the basis for my interest in mythic studies and mythic literacy, much of which has influenced my poetry writing as well.

3. What experiences and inspirations led you to create your blog? How has technology and the Internet revolutionized the way we share and participate in cultural phenomenon, such as Afrofuturism? What challenges are created by technology and the Internet?

The inspirations for my blog, Futuristically Ancient, came during my junior year in college. At that time, I was in a blogging class with Bridget Davis and the final assignment was to start our own blogs. I was thinking about what kind of blog I wanted to do, and I remembered watching a small portion on Youtube of John Akomfrah’s The Last Angel of History and I liked the connections it made between the past, present and future of the Diaspora through the investigation of memory, music and digital technology. So, I centered my blog around those ideas at first before I even knew the term Afrofuturism. But as I began to research more into related materials to his film and while doing research for my thesis, I came across the term Afrofuturism, and then my blog developed into what it is now. The name of my blog actually comes from a phrase someone had used to describe poet Aja Monet and it stuck with me, so I used it in addition to Aker, the Egyptian god of the horizon representing yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Technology, especially the Internet, has played a significant part in the spread of information about Afrofuturism and other cultural phenomena. Personally, as a blogger, writer and researcher, it has allowed me to voice thoughts and ideas that I rarely saw in popular spaces and share them with others in ways I would not have been as easily able to do before; it has allowed me to connect with others who are working in similar fields or whose work has similar tendencies; it has allowed me to more easily find materials and information, especially rare ones, to share on my blog and to use for research. So, it has been helpful to a person like me, who is introverted and kind of shy, to be able to put myself out there on my own terms. Like me, others have benefited from the more accessible information and connection to people all over the world through new technology and the Internet, which has allowed ideas about Afrofuturism to spread fast.

However, as with anything, there are downsides to technology and the Internet. People will use technology and the Internet to try to discourage us, to attack us because they see what we are doing as a threat to their way of life, to try to silence us especially if they have more capital and power to do so, to use our ideas to sell their own agenda without crediting us or to use our ideas against us. In some ways, old oppressions are magnified through the Internet and new technology because of how quickly and easily information can spread.

4. Where do you see Afrofuturism 10 years from now? How can marginalized communities and youth gain more access to Afrofuturism?

Ten years from now, Afrofuturism can go in different possible ways. It could become bigger and go mainstream to the point it is diluted and appropriated so much that it lacks power and we move on to the next movement, term, idea or whatever. Maybe it will have another or several names 10 years from now. Or hopefully, it can evolve and grow along with the changes in our cultures and technologies, which is why I like that it does not have a fixed definition. I want us to continue defining it for ourselves, especially with the controversy over the origin of the term. I want Afrofuturism to change and shape shift into various meanings depending on the different localities it reaches and how it can best benefit them. As Octavia Butler wrote, “God is change,” let Afrofuturism do that as well.

As for marginalized communities and youth gaining access to it, gatekeepers who have closer access or are in more privileged spaces need to continue sharing it and the ideas within it with those who are more marginalized or younger. For example, in the art world, much of the art tends to stay in higher-class institutions that are either out of reach or out of the means of more marginalized groups. That is why I like to go to events at museums or other institutions and review them, so at least some of the information discussed is available online for others who may not have access to them can learn.

But in the opposite direction, marginalized communities and youth should be encouraged to explore outside of the boxes that are placed on them. Our cultures need to not limit our freedom of expression and questioning, as I have seen in some spaces, like often the church. Explore the world around you, the worlds alien to you, in any way you can, whether it is traveling to another town or to a place in your neighborhood you never went before, going to the library and getting a book that is outside of what you normally read, or even thinking an unconventional thought on a common thing. Keep an open mind to the various possibilities of the world outside of your own direct reality.

Those ideas to me are already inherent in Afrofuturism – the need to explore and to invent, even if it is only in your head. Afrofuturism is just a new term for many of things we already do, but are either told we don’t do, suppress them or don’t realize it. We use our memories of our pasts and traditions of our cultures, reshape them and build new futures out of them in the new places we disperse and in the face of new crises and limitations of survival.

Rasheedah Phillips is a Philadelphia public interest attorney, speculative fiction writer, the creator of The AfroFuturist Affair, and a founding member of Metropolarity.net. She recently independently published her first speculative fiction collection, “Recurrence Plot (and Other Time Travel Tales).”