As science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) careers continue to struggle to become more diverse, a young Black math prodigy is demolishing every stereotype that this industry has held against Black women specifically and black people in general.

Past diversity reports from today’s biggest tech giants say it all — Black people and women are grossly underrepresented in STEM fields.

It’s a pattern that is reflected all throughout the STEM industry.

This means Black women in such fields are nearly impossible to come by, but as one 10-year-old math prodigy is proving, it’s not because Black women aren’t capable of filling these positions.

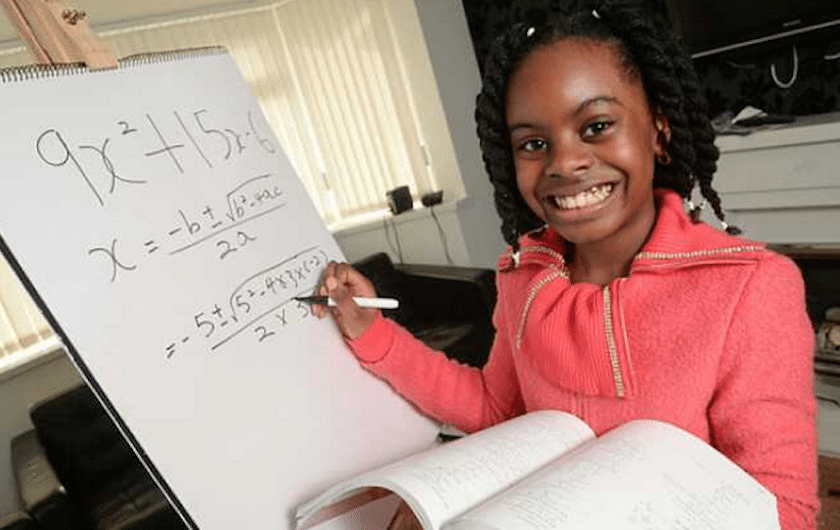

Esther Okade of Walsall, England, would likely be shocked to hear of the deficit of Black women in STEM, if she hasn’t heard about the serious shortage already.

While the general consensus and illegitimate stereotypes have led people to believe that Black girls just aren’t into math, Esther spends much of her time ripping through equations and formulas that would leave her college classmates stumped.

Yes. Her college classmates.

Before she even reached her teenage years, Esther managed to successfully enroll in the U.K.’s Open University, a distance learning and research university, where she will be working toward a mathematics degree, the Telegraph reported.

“I just love math,” Esther told the Daily Mail about her recent accomplishment and obsession with numbers. “All the numbers and the solving, it’s like a mystery.”

Math isn’t the only interest Esther has. Outside of being able to crunch numbers like a seasoned accountant, she has the same interests that any other 10-year-old would have.

Esther told the Telegraph that she enjoys playing with dolls and is in love with the movie Frozen.

But in the midst of watching her favorite talking snowman and playing with friends, she’s preparing to become a successful banker.

She estimates that she’ll be able to earn her degree in roughly two years before going on to earn her Ph.D.

“And then from there I’ll start running my own business,” she added, according to the Daily Mail. “I want to be a banker.”

For those who are concerned that this could be an overwhelming experience for the young math genius, her mother wants the world to know that this was all her daughter’s decision.

“From the age of 7, Esther has wanted to go to university,” the math prodigy’s mother told the Telegraph. “But I was afraid it was too soon.”

Eventually, she just couldn’t say no anymore.

Esther begged her mother to allow her to go to the university and finally receive a challenge in the classroom when it came to math — even though those challenges still haven’t left Esther struggling by any means.

On a recent exam, Esther received a perfect score.

Industry experts are hoping that the young aspiring banker will be enough to encourage other young Black girls to ignore messages that the STEM field isn’t for them.

Boys are far more likely to be encouraged to pursue such careers, which plants the necessary seeds of interest at a young age. Young Black girls are typically left out of that conversation and rarely discover their interest in STEM until they are much older, if even then.

But as young Esther has demonstrated to the world, it’s about time that more young Black girls are encouraged to give STEM careers a try.

After all, leaving more great minds like Esther’s out of the mix and away from STEM jobs in the future would only be cheating the entire world out of the possible innovations that their work could bring to the industry.