In the midst of what has grown to be a serious shortage of doctors and medical practitioners in South Africa, the country is relying heavily on natives to return to rural parts of the country to help provide quality health care to those who need it the most.

Recent statistics paint a very troubling picture of health care in rural parts of South Africa.

In addition to proving that there aren’t enough doctors to go around, there is also evidence suggesting that only the doctors who grew up in these rural areas are likely to return and work there.

Only 12 percent of the country’s physicians work in rural areas despite the fact that more than 45 percent of the country’s population lives in rural areas.

The shortage of medical practitioners means patients are waiting much longer to receive care despite the fact that people in these areas tend to be much more seriously ill than those in more urban parts of the country, according to a 2009 study published in the health journal Rural and Remote Health.

Only doctors who have a particular connection to the rural parts of the country seem to be willing to work there, leaving the people relying heavily on doctors like Llewellyn Volmink.

Volmink grew up in a rural South African town called Ladismith and witnessed the death of his own grandfather when he was still just a 14-year-old boy.

His grandfather had been stabbed in the neck by a relative and as Volmink watched the ambulance carry his body away, he realized then that he wanted to be a doctor, according to the Mail & Guardian.

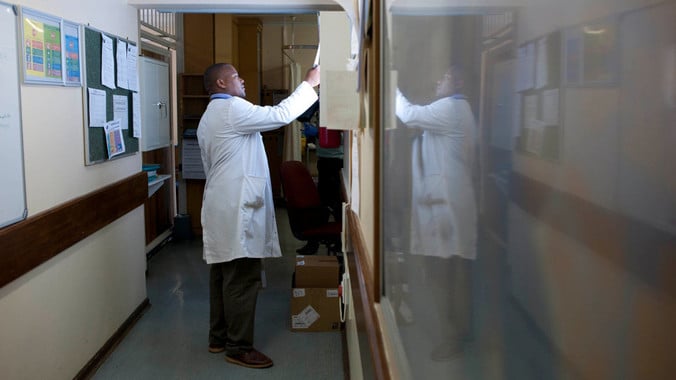

Volmink is now 27-years-old and has followed through on his dream to become a doctor.

Unlike many in his position, he had decided to focus on rural parts of South Africa to help provide his countrymen with the medical assistance they so desperately need.

The ratio of people to medical practitioners in rural parts of South Africa is disheartening and well below the country’s national average.

While the nation averages 30 doctors and 30 specialists per 100,000 people, rural parts of the country average only 13 general practitioners and two specialists per 100,000.

This means rural areas have a disproportionately lower amount of doctors despite the fact that the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests these areas should actually have a disproportionately higher number of doctors based on the seriousness of the illnesses that patients in these areas tend to have.

After years of trying to solve the patient-to-doctor deficit, it seems the real key lies in getting future medical practitioners to experience these rural areas for themselves.

Studies in the United States, New Zealand, Australia, China and the Democratic Republic of Congo all proved that exposure to such rural areas during an individual’s undergrad years drastically increases the likelihood of them returning to those areas to work in the future, regardless of their own upbringings.

By getting students to spend more time in these areas, there are not only hopes that they will return to practice medicine there but also that they will pick up on the native language and become a true asset to the region’s healthcare efforts.

In addition to not having enough doctors, rural areas have fewer doctors who can speak the native tongue of the patients, which makes it incredibly difficult to give the proper medical care.

This is why Volmink is such a highly respected member of the medical community in his hometown.

The trilingual doctor is able to fluently speak English, Afrikaans and Xhosa, a language that many doctors in the areas don’t speak.

“It’s my role to explain to patients, in their own language, and like a lay person, what is wrong with them and how we’re going to help them,” Volmink said.

He went on to say that since he is the only doctor at his hospital who speaks Xhosa, he is often called in to translate for patients throughout the day, which makes it easier for doctors to help patients but also adds some extra pressure on Volmink.

“When a Xhosa patient arrives, I get called, because they are able to explain to me in the language they are most comfortable with why they’ve come to the hospital,” he said. “It makes it easier for us to help them. We provide a much better service when we communicate with them in their home language.”

Volmink and other doctors who made the decision to return to the rural areas they grew up in hope they can combat the depleting numbers of medical practitioners in rural communities all across the globe.